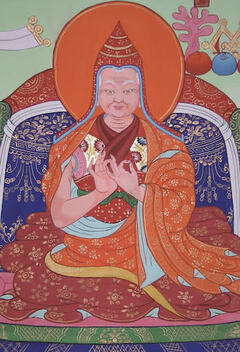

Dzogchen Khenpo Lhagyal Biography

The Biography of Dzogchen Khenchen Abu Lhagang (1879–1955)

by Khenpo Tsöndrü

The birthplace of the glorious and kind Khenchen Pema Tekchok Loden, also known as Dzogchen Khen Lhagyel or Lhagang, was in the Dzogchen Drogri valley. The names of his parents, his birth year, and other details are unknown.[1] Both Dzogchen Khenpo Chime Rinpoche[2] and Khenpo Chönam Rinpoche[3] were his nephews, as was a monk called Wangchuk Tsering, who was proficient in the scriptures. When two of his younger nephews were recognized as the emanations of Do Rinpoche, Khenchen Tekchok said: “Whether or not they are emanations, they should become monks. It is customary in our family lineage for there to be proper monastics.” As this indicates, he was certainly born into a family lineage with a naturally good [standing].

There is a reliable account reported by two senior disciples that Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo[4] had a clear indication in a dream while he was staying at Dzogchen Monastery that Pema Tekchok Loden was one of the emanations of the great paṇḍita Vimalamitra, who appears in Tibet once every hundred years.

Dokham’s crown ornament of scholars and adepts, Patrul Jigme Chökyi Wangpo,[5] had four disciples who were superior to himself.[6] Pema Tekchok Loden’s exceptional gurus included one of these, Önpo Tenga, or Orgyen Tendzin Norbu,[7] who surpassed his teacher in the [philosophy of] the Middle Way, as well as his direct disciple Dzogchen Khenpo Shenga, or Khenchen Shenpen Chökyi Nangwa.[8] The master also had a mutual guru-disciple relationship with the great destroyer of delusion Galen Lama Kunga Pelden.[9] He served at the lotus feet of many particularly noble, spiritual mentors including the Fifth Dzogchen Tubten Chökyi Dorje[10] and Jamyang Mipham Chokle Namgyel,[11] as well as listening to and contemplating sūtras and tantras along with the general fields of knowledge. He thus became a lord of scholars. In particular, he acquired a clear understanding of [Dharmakīrti’s] Seven Treatises (sde bdun) and the root texts and commentarial literature of the sūtras. He became known as an exceptional scholar of valid cognition, authoritative in exposition, debate, and composition.

For eight years he served as the abbot of the main Dzogchen Monastery and Śrī Siṃha College. He continued his enlightened activities by primarily explaining and propagating the thirteen great classics of Indian [Mahāyāna philosophical] scriptures, as well as the sūtras, tantras, and fields of knowledge. Thereafter, he devoted the remainder of his life to practice in what is known as the Yamāntaka Meditation Cave, a cave near Dzogchen Monastery where the long mantras of Vajrakīlaya and Yamāntaka as well as the seed syllable of Yamarāja naturally appeared. This is also where the dharma lord Patrul Rinpoche wrote The Words of My Perfect Teacher: An Instructional Manual for the Preliminary Practices of the Longchen Nyingtik and conducted a long retreat, which imbued the cave with blessings.

Pema Tekchok travelled twice to Dzogchen Monastery when others requested him to do so and it was of some significance for the benefit of the teachings. But besides these two occasions, he never left and stayed exclusively in seclusion in that sacred place. He had a square bed with a blanket, which was perfectly suitable for his cross-legged posture. He strove in meditation and never fully loosened his belt [to sleep]. He owned only a tea kettle, a bag for roasted barley flour, and some baskets, and didn’t accept any common worldly provisions. He devoted himself solely to the conduct through which one renounces all things and is freed from activities.

When people gave him offerings on behalf of the dead, he would never accept large donations, only small ones, and even these were used as offerings for such things as celebrating the anniversary of the omniscient master, making feast offerings and so forth; he would not use them to fund his own resources. He didn’t eat meat. During the summer, he would sit naked and offer his blood to the blood-drinking insects of the forest. When there was moonlight at night, he would place his yogic meditation pad upon a boulder and practice the physical yogas; so much so that the boulder even grew smaller as a result.

Between sessions, he boundlessly bestowed the nectar of profound instructions on faithful people from all directions, gaining countless disciples, including abbots and tulkus who preserved and held the doctrine of the victors and hermits who had given up life’s concerns and were free from activities. Even Khunu Lama Tendzin Gyaltsen Rinpoche said recently that he was Pema Tekchok’s student and that it was from him that he received the entirety of the Dzogchen Nyingtik’s instructional cycles.

So exceedingly profound was his mind that the depth of his realization is difficult to comprehend. Still, we can consider what I believe to have been the core of his practice: all the instructions and profound advice from the textual tradition of the Omniscient One [Longchenpa Drimé Özer] and his heir [Jigme Lingpa],[12] the creation stage practices of the three yogas based upon the three roots of The Heart Essence of the Great Expanse (Longchen Nyingtik), and the completion stage practices of wind-energy according to the aural lineage based upon the primordial wisdom deity (jñānasattva) from the Assembly of Vidyādharas (Rigdzin Düpa), as well as The Four Works of the Heart Essence (Nyingtik Yabzhi), especially The Guru’s Inner Essence (Lama Yangtik) and The Heart Essence of the Ḍākinī (Khandro Nyingtik), as well as The Unexcelled Primordial Wisdom (Yeshe Lama), and the Seven Treasuries, especially the Treasury of the Dharmadhātu (Chöying Dzö). In any case, he became a great lord of realization, and at that time he was the source for clearing up misconceptions of [meditative] experiences and realizations for the majority of scholars and adepts in his vicinity including Shechen Kongtrul Rinpoche.[13]

As a sign that his material body had been liberated into a body of light, he never cast a shadow. As an indication of his accomplishment of the supreme inner heat (tummo), his water offerings never froze even in the bitter cold of winter, and people who came within his vicinity could feel the naturally arising heat within a bowshot of his dwelling. Since his training in discipline was as pure as the inner space of a lotus bulb, the sweet fragrance of discipline also permeated for about a bowshot. These signs were directly apparent. There were also well-known stories about the effectiveness of his blessings, such as how his protection cords could fend off weapons and prevent infant mortality.

In brief, he was like a great moon of a Dharma teacher, in whom the qualities of scholarship, standing as a reverend monk, signs of accomplishment, kind deeds, and other sacred qualities were all fully complete. He was a crown ornament among myriad wish-fulfilling scholars and adepts, the primordial Buddha Samantabhadra manifesting in the form of a spiritual master, inseparable from the omniscient Drimé Özer (Longchenpa). Having reached the full extent of his life and practice, he became fully enlightened within the space of peace.

| Translated by Ryan Jacobson, Tenzin Choephel, and Tom Greensmith, 2020.

Bibliography

Textual Sources

thub bstan brtson 'grus. 1985?. "rdzogs chen mkhan lha rgyal lam lha dgongs su grags pa'i mkhan chen pad+ma theg mchog blo ldan dpal bzang po'i rnam thar." In gsung 'bum/ thub bstan brtson 'grus, vol. 1, pp. 67–72. Bylakuppe: Nyingmapa Monastery. BDRC W10200.

_____ . "rdzogs chen mkhan chen a bu lha sgang gi rnam thar". In mkhan chen thub bstan brtson ‘grus kyi gsung ’bum. 2 volumes. Lhasa: Bod ljongs bod yig dpe rnying dpe skrun khang. 2011. Vol. 2: 225–228.

Version: 1.2-20250219

-

More information about the life of Khenchen Pema Tekchok Loden, including his dates and the names of his parents, has become available since this biography was written. For a full biography that incorporates the latest findings see Ryan M Jacobson, "Pema Tekchok Loden," Treasury of Lives, accessed September 28, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Pema-Tekchok-Loden/9585. ↩

-

See Samten Chhosphel, "Chime Yeshe," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 18, 2020 http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Chime-Yeshe/9589. ↩

-

See Samten Chhosphel, "Chonam," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 18, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Chonam/5121. ↩

-

See Alexander Gardner, "Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 18, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Jamyang-Khyentse-Wangpo/4291. ↩

-

See Joshua Schapiro, "Patrul Orgyen Jigme Chokyi Wangpo," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 18, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Patrul-Orgyen-Jigme-Chokyi-Wangpo/4425. ↩

-

In addition, Nyoshul Lungtok Tenpai Nyima (smyo shul lung rtogs bstan pa'i nyi ma, 1829–1901/2) is said to have surpassed his teacher in view; Gyalrong Tendzin Drakpa (rgyal rong bstan 'dzin grags pa, 1847/8–c.1921) surpassed his teacher in logic and epistemology; Minyak Kunzang Sonam (1823–1905) surpassed him in teaching the Bodhicaryāvatāra. ↩

-

See Adam Pearcey, "Orgyen Tendzin Norbu,"Treasury of Lives, accessed August 18, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Orgyen-Tendzin-Norbu/7551. ↩

-

See Samten Chhosphel, "Zhenpen Chokyi Nangwa," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 18, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Zhenpen-Chokyi-Nangwa/9622. ↩

-

See Ryan M Jacobson and Tenzin Choephel, "Kunga Pelden," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 19, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Kunga-Pelden/9594. ↩

-

See Ron Garry, "The Fifth Dzogchen Drubwang, Tubten Chokyi Dorje," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 19, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Dzogchen-Drubwang-05-Tubten-Chokyi-Dorje/9646. ↩

-

See Douglas Duckworth, "Mipam Gyatso," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 19, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Mipam-Gyatso/4228. ↩

-

Alexander Gardner, "Jigme Lingpa," Treasury of Lives, accessed August 19, 2020, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Jigme-Lingpa/5457. ↩