Opening the Door of Dharma

Opening the Door of Dharma

A Brief Discourse on the Essence of All Vehicles

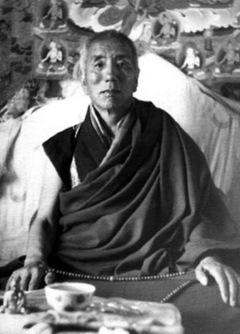

by Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö

Homage to the guru and the protector Mañjughoṣa!

You tear right through the web of self-oriented views,

And your sword of wisdom lights up the triple world—

Great store of all the victorious buddhas' insight,

Protector Mañjughoṣa, to you I pay homage.

I could not describe all dharma systems

Of the infinite vehicles beyond imagining,

But I shall offer here a mere sketch,

A partial overview in a succinct style.

The omniscient teacher, Lion of the Śākyas,

Turned the Wheel of Dharma in three stages:

The first was to counter the non-meritorious,

The intermediate to counter views of self,

And the last to counter all foundations of views.

The subject matter, which is the three trainings,

Is explained through the twelve branches of excellent speech.[1]

While some refer to the great vehicle of Secret Mantra

As the Inner Abhidharma, it is said to be

The scriptural category of the vidyādharas.

Counting it separately like this is maintained to be better.

Translations into Tibetan amount to just over a hundred volumes,

But the true extent of the Buddha's Word cannot be gauged.

The treatises that comment on the intent of Buddha's teachings

Include the Basic Vehicle's Treasury of Detailed Classification,[2]

And the Great Vehicle's commentaries by such scholars as

The Six Ornaments of the World[3] and Marvellous Masters[4]—

An exceedingly large number of compositions in all.

There are also commentaries on the tantras of Secret Mantra,

Sādhanas and pith instructions in number beyond imagining.

Through the kindness of the translators and paṇḍitas of the past,

Over two hundred volumes of these were translated into Tibetan.

All together they have served as the basis of the teachings.

In the Noble Land there was no distinction between New and Old.

In Tibet, as lotsāwas translated in earlier and later phases,

The Old-New distinction arose, with the period before Rinchen Zangpo

Designated the time of the Ancient School of Early Translations,

And the translations of the period thereafter referred to as New.

Most of the Vinaya, Sūtra and Abhidharma collections,

As well as the three outer tantra classes of Secret Mantra,

Were translated during the period of the Early Transmission.

Highest Yoga tantras such as Saṃvara, Hevajra, Kālacakra and Yamāntaka

Were translated mostly in the later period, but the Ancient School of Early Translations

Also has a very large number of Highest Yoga tantras,

Such as the eighteen great tantras.[5]

Although some scholars of the New Schools have stated

That these tantras are inauthentic,

The impartial understand them to be genuine.

Indeed, I think it is correct to do so.

Why? Because these texts accurately convey the profound and vast points

Of the Buddha's Word and the treatises,

And it is only right, therefore, to honour and respect them.

In the Ancient School of Secret Mantra there are nine successive yānas,

Which can be subdivided into two: the causal and resultant vehicles.

There are three causal vehicles: those of the śrāvakas, pratyekabuddhas and bodhisattvas.

And the resultant mantra vehicle includes three classes of outer tantra,

And three classes of inner tantras, which employ vast methods.

There are many further details for each of these,

Such as their respective views, meditation, conduct and results,

But since this is only a brief survey I cannot elaborate here.

The Ancient School of Early Translations has three categories of Word (kama), Treasures (terma) and Pure Visions.

The New School of Secret Mantra is also called the Jowo Kadam tradition.

Its members included Atiśa, Gyalwa Dromtönpa,

The Three Brothers,[6] and countless other holders of the teachings.

The Old Kadam became intermingled with the Sakya and Kagyü.[7]

Taking this as a basis, Jamyang Tsongkhapa

Expanded upon Vinaya, Sūtra, Madhyamaka, Prajñāpāramitā, Secret Mantra and so on,

And his tradition spread everywhere throughout the whole world.

He made profound statements concerning sūtra and mantra

With the aid of his special deity and through his own discerning insight,

And special qualities are clearly evident in his excellent explanations.

The Sakyapa, which was founded by the five venerable patriarchs,[8]

Upholds the sūtra and mantra tradition of many learned and accomplished ones

Of the Noble Land, such as the great lord of yogins Virūpa,

Nāropa and Vajrāsana,[9] as well as the Yangdak and Kīlaya practices

Of the Ancient School of Early Translations, which belong to the so-called Khön Tradition.

Sakya Paṇḍita, who was the crown jewel of all the scholars of this world,

Defeated a heretic, Harinanda, in debate—

A feat no one else is known to have accomplished in Tibet.

There are three branches that uphold this lineage: Sakya, Ngor and Tsar.

Butön's tradition (Buluk), the Jonang and the Bodong also stem

From the foundation of the Sakya school,

Albeit with some slight divergence in their views on sūtra and mantra.

The Kagyü School derives from Nāropa and Maitrīpa.

Marpa, Mila and Dakpo are the three lords of all Kagyüpas.

It is from them that the four major and eight minor branches

And others derive, although most stem from Dakpo's student Pakmodrupa.

And among them, four still remain strong and undiminished to this day—

The Karma, Drukpa, Drikung and Taklung—

While the others have grown extremely weak indeed.

The scholar-adept known as Khyungpo Naljor

Followed a hundred and fifty learned and accomplished teachers,

Including the two wisdom ḍākinīs of India,[10]

The masters Rāhula and Maitrīpa, and others.

When transmitted in Tibet, his teachings became the Shangpa Kagyü.

There is no one today who follows this tradition exclusively,

But the empowerments and reading transmissions continue in both Sakya and Kagyü.

In addition, there is the Pacifying tradition

Of the Indian known as Dampa Sangye,

And Severance (Chöd), the Dharma of Machik Labdrön.

There are thus a great many systems of Dharma teaching in Tibet,

But aside from their nominal variations,

There is really no significant difference between them—

All share the crucial point of seeking ultimate awakening.

It is said that the Sakya and Gelug have a special command of teaching,

While the Kagyü and Nyingma have a special command of practice.

But, in fact, the scholars of former times put it like this:

The Nyingma opened the way to the teachings in the Land of Snows.

The Kadam became the source of millions of holders of the teachings.

The Sakyapas are the ones to spread the teachings in their entirety.

The Kagyü are unrivalled in the direct path[11] of practice.

Tsongkhapa was sun-like in his brilliant conveyance of fine explanations.

Jonang and Zhalu were sovereigns of the profound and vast tantra collection.

This account matches how things are in reality.

The treasures of the Nyingma school are teachings,

Common and uncommon, which Padmasambhava,

The great master of Oḍḍiyāna, gave upon arrival in Tibet

To his disciples, the sovereign lord and subjects,

And which were then concealed as earth and mind treasures

To support the teachings and beings during the degenerate age.

When the time is right, they are revealed by sublime incarnations

And serve as bounty for the welfare of the teachings and beings.

There are many examples of 'pure visions' and 'whispered transmissions'

In both the Ancient and New traditions of Secret Mantra.

Some scholars have argued against the validity of the treasures.

However, since an examination of their purpose and underlying intention

Establishes the threefold validity of the terma teachings,[12]

One must be careful to avoid denigrating them

And thereby incurring the grievous fault of hostility toward the Dharma.

The One Hundred Thousand Lines and so on were Nāgārjuna's treasures,

And adepts extracted tantric texts of secret mantra

From the stūpa of Dhumathala in Oḍḍiyāna.

Even in the Noble Land, then, treasure revelation existed.

There are many other such proofs, but I shall not elaborate further.

The Path

For all the systems of teachings described above,

The essence of the path is to generate renunciation.

For this, the basis is to maintain ethical discipline

According to any of the seven sets of pratimokṣa vows

And to contemplate the rarity of the freedoms and advantages.

The Freedoms and Advantages

Reflect carefully on how difficult it will be to obtain[13]

Such an excellent support and opportunity again in the future.

It is momentous to find something so scarce, like a wish-granting jewel.

Death and Impermanence

Yet this situation will not last long, as death comes quickly.

There's no telling when the old, young or middle-aged will die,

For many circumstances lead to death, while few sustain life.

Reflect repeatedly on the passage of time, changing of the seasons,

And inconstancy of rivalries and friendships, and recollect impermanence.

Actions and Their Effects

After death, we do not simply vanish into the ether.

Nor are human beings necessarily reborn as humans and horses as horses.

Wandering beings are propelled by their past actions.[14]

The variety that exists among beings—in status and condition,

Relative affluence or poverty and range of influence,

As well as variations in physical beauty and appearance—

All originates in the variety of our past karma,

Which may be virtuous, unvirtuous or mixed.

Virtuous and unvirtuous deeds are of ten types.

Based on the four types of effect—ripening, cause-resembling, conditioning and proliferating—

Virtuous and unvirtuous acts give rise to particular results.

We do not encounter the fruits of deeds we have not committed;

The acts we have committed will never go to waste;

And the agent of an action is sure to face its consequences.

For a more detailed presentation of actions and their effects,

Including actions that bring about effects within the same life,

And acts that ripen in the next or subsequent lives,

Please consult the sūtras, treatises or guidance manuals.

To adopt and avoid certain actions and their effects

Is the essence of the Dharma and a profound key point

Which encapsulates the four truths and dependent origination.

The Trials of Saṃsāra

Through karmic acts we wander through the six classes of beings,

Which consist of the three lower and three upper realms.

To put it simply, there is nothing, not even so much as an atom,

Throughout the desire, form and formless realms that is without fault.[15]

Beings everywhere are tormented by the suffering of suffering,

Suffering of change and all-pervasive suffering of conditioning,

And each of the six classes has its own particular tribulations.

Non-virtue produces suffering as its effect;

Tainted virtue leads to rebirth in the higher realms;

And undeviating acts of mundane meditative absorption

Cast one into corresponding dhyāna and formless realms.

But, as the source of saṃsāric existence has not yet been discarded,

Craving and attachment propel one into existence, and one falls back into saṃsāra.

To stay in these states of cyclic existence, therefore,

Is akin to remaining in a pit of flames or a nest of vipers.

Do not hanker after the pleasures of saṃsāra,

But develop the determination to escape conditioned being.

Following a Teacher

The basis for setting out on the path to liberation

Is to follow and rely upon a spiritual teacher—

Subdued through study, ethical, steeped in bodhicitta,

With a pure and genuine view, immensely caring,

Capable of cutting through projections, empowered, and upholding the samayas.

Follow such a guru and carry out his or her every command.

Developing faith and devotion brings positive qualities,

So it is crucial that you follow an excellent guru.

The teacher's instructions are like the nectar of immortality:

Do not allow whatever you receive to go to waste,

But put it all into practice, reflect on it and meditate.

Hearing alone is not sufficient to bring benefit,

Just as thirst cannot be quenched without drinking.

So remain in solitary retreat upon a mountainside.

Taking Refuge

The foundation of the path is taking refuge.

This is the basis of, and support for, all vows;

It is what separates Buddhists from non-Buddhist outsiders,

And affords protection to all gods and human beings.[16]

It is what brings all that is positive in this life and beyond.

Entrust yourself entirely to the Buddha as teacher,

Sacred Dharma as protection, and Saṅgha as guides.

Do not simply mouth the words, but feel genuine trust,

And guard the precepts of refuge effectively.

Generating Bodhicitta

The main practice of the Mahāyāna path is bodhicitta—

Like butter that emerges when sacred Dharma milk is churned.

Without it, any practice of sūtra or mantra which we may do

Will be devoid of essence, like the stalk of a plantain.

In addition, beings who exist throughout the whole of space

Have, over the course of our countless lives without beginning,

Been our very own parents innumerable times

And brought us benefit that is truly unimaginable.

Cultivate love, therefore, and great compassion

For all beings—friends, enemies and those in-between.

Fully dedicate your body, speech and mind to virtue,

Cultivate the excellent intention of benefitting others,

And continually recite extraordinarily noble aspirations.

Accumulation of Merit and Purification

It is crucial that, as a means of developing the authentic view,

You apply yourself to accumulating merit and purifying obscurations.

Perform the seven branches, offer prostrations, circumambulate, chant sūtras,

Recite dhāraṇī mantras and the Bodhisattva's Confession of Downfalls.

If you exert yourself with all four powers complete,[17]

You will cleanse and purify misdeeds, obscurations, faults and downfalls.

Make maṇḍala offerings, the essence of gathering the accumulations.

For all such accumulations with conceptual reference,

To recognize how the three spheres are devoid of reality,

And integrate emptiness by means of insight

Brings about the accumulation of wisdom.

The accumulation of merit brings attainment of the rūpakāya,

And accumulation of wisdom brings attainment of dharmakāya.

Śamatha Meditation

In order to strive for accumulation and purification like this

And to bring about the genuine view within the mind,

First seek calm abiding (śamatha) through the nine stages,[18]

Overcoming the five faults[19] and applying the eight remedies.[20]

And when there is single-pointed focus with and without support,

Absorption—blissful, clear, and non-conceptual—will arise.

This itself serves merely to suppress mental afflictions.

Vipaśyanā Meditation

Then, because ascertaining the view with insight (vipaśyanā)

Eradicates the ignorance of clinging to a self,

Which is at the root of beginningless existence,

You should meditate upon emptiness with certainty.

In order to overcome innate clinging to a self,

Which is the thought of "I am" that arises

Based on the assembly of the five aggregates,

It is crucial to apply precise and thorough analysis.

Investigate using the logical reasoning of the Middle Way

Whether self and aggregates are identical or distinct, and so on.

When you thus determine the absence of an individual self,

Consider the identity of perceiving and perceived phenomena,

By mentally dissecting the aggregates further into their component parts.

And, gaining conviction in the meaning of identitylessness,

Determine how all the phenomena of existence and quiescence

Are by nature unborn.

Understand the profound logic of dependent origination—

How everything originates in perfect equality,

And how, out a state of unborn emptiness,

Visible and audible phenomena arise naturally, without obstruction.

When you gain understanding and experience

Of how emptiness is not separate from dependent origination,

Then, untainted by any grasping, settle for as long as you can

In the space of the Middle Way, free from conceptual elaboration.

In short, what we call the genuine view

Is the inseparable unity of wise insight

And single-pointed, immovable calm,

In which there is discerning intelligence

That alternates between analysis and rest.

This is the point of meditation on Prajñāpāramitā,

The mother of all the buddhas.

Through the view beyond all concepts such as the eight extremes,[21]

The meditation of settling in accordance with this undistractedly,

And the action of the excellent noble path of the bohisattvas,

We achieve the results of the five paths and ten stages,

Gain the great awakening that is situated in neither existence nor quiescence,

And spontaneously accomplish our own and others' welfare.

Nonsectarianism

Alas! Nowadays, during this final stage of the five degenerations,

Many holders of the teachings have passed into the absolute sphere,

And the world is filled with people like me who spout nonsense.

The asuras are raucous in their laughter,

And beneficent deities have scattered and fled.

Now that the Buddha's teachings resemble nothing more than a painted lamp,

May those with great compassion pay heed.

All those who cherish the teachings of the Buddha

Should exert themselves in teaching and practising the transmitted and realized Dharma, and in renunciation, study and activity.

Never should they neglect the ten dharmic activities,[22]

And they must endeavour to pray, make offerings and accumulate merit.

Saṅghas must be harmonious and avoid sectarian bickering.

Do not be partial or divisive, and do not promote conflict in the teachings.

Avoid all denigration of the Dharma.

Recognise that all the various facets of the teachings, as extensive as the ocean,

Are there to discipline one's own mind, and practise them accordingly.

With body, speech and mind calm, disciplined and relaxed,

Always maintain mindfulness, vigilance and conscientiousness.

In accordance with the prophetic dream of King Kṛkin,[23]

Eighteen schools arose among the śrāvakas in the Noble Land,

Bringing disagreement to the teachings,

As a result of which they gradually declined.

In Tibet, to the north, the demon of sectarianism

Entered the Sakya, Gelug, Kagyü and Nyingma,

And disputes marred and corrupted the teachings,

Ruining present and future lives and leading self and others to wrongdoing.

Since this is not even slightly connected to the real point,

It should be roundly rejected as one guards the Buddha's teachings.

As a result of the Buddha's attainment of the level of fearlessness,

No one can destroy the teachings from the outside.[24]

But, as the sūtras say, they may still be ruined from within,

Like the carcass of a lion devoured by worms in its belly.

So keep this in mind, and adopt and avoid as you should.

If householders make offerings to the Three Jewels

And, with a wish to benefit, exert themselves in virtue,

This will bring about merit in this and all future lives.

I am now close to death and burdened by old age.

Although I have noble aspirations for the Buddha's teachings,

I certainly lack any capacity to bring real benefit.

Still, I shall persevere in praying for the Dharma to flourish.

The supreme source of benefit and happiness in the Land of Snows

Is Tenzin Gyatso—may his life long remain secure.

May the Paṇchen Lama, the protector Amitābha,

As well as the Karmapa, Jamgön Sakyapa,

And other great holders of the teachings all live long.

May all their enlightened activity flourish and spread.

May the rulers, ministers and subjects of the Noble Land

Enjoy the happiness, splendour and prosperity of a golden age,

And may the Buddha's teachings once again spread widely.

May the great Dharma drum of the three scriptural collections resound,

And may all be auspicious for it to reach even unto the pinnacle of existence.

Thus, this Opening of the Door of the Dharma

Was written extemporaneously with a noble intention

At the request of the Political Office of Sikkim,[25]

By the ignoramus Chökyi Lodrö,

Who holds the name of an incarnation of Jamyang Khyentse

And hails from the land of greater Tibet.

May the virtue of this be of aid to the teachings and beings.

Sarvadā maṅgalaṃ! Śubhaṃ!

| Translated by Adam Pearcey, 2020, with the generous support of the Khyentse Foundation and Terton Sogyal Trust.

Bibliography

Tibetan Editions Used

gSung 'bum – 'Jam dbyangs chos kyi blo gros. "'Theg pa mtha' dag gi snying po mdo tsam brjod pa chos kyi sgo 'byed" In 'Jam dbyangs chos kyi blo gros kyi gsung 'bum. 12 vols. BDRC W1KG12986. Bir, H.P.: Khyentse Labrang, 2012. Vol. 9: 49–64.

bSam 'phel – 'Jam dbyangs chos kyi blo gros. Theg pa mtha' dag gi snying po mdo tsam brjod pa chos kyi sgo 'byed. BDRC W1KG3866. 1 vols. [s.l.]: [bsam 'phel nor bu], [n.d.].

Secondary Sources

Aris, Michael. 1977. “Jamyang Khyentse’s Brief Discourse on the Essence of All the Ways: A Work of the Ris-med Movement” in Kailash, 5 no. 3. pp. 205–228

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro. Opening the Dharma: A Brief Explanation of the Limitless Vehicles of the Buddha. (trans. Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Gyatso. Edited and annotated by Diane Bowen, assisted by Yong Siew-Chin). Gyalshing, India: Dzongsar Library, Dzongsar Institute, 1984

Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche Cho-kyi Lodoe. "Opening of the Dharma: A Brief Explanation of the Essence of the Buddha's Many Vehicles" (trans. Geshey Ngawang Dhargay, Sharpa Tulku, Khamlung Tulku, Alexander Berzin and Jonathan Landaw in H.H. the Dalai Lama, First Panchen Lama, Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche and Kalu Rinpoche. Four Essential Buddhist Texts, New Delhi: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1982 (revised edition, first published 1981). pp. 3–22

Version: 1.4-20250601

-

gsung rab yan lag bcu gnyis. 1) sūtras; 2) poetic summaries (geya); 3) prophecies (vyākaraṇa); 4) discourses in verse (gāthā); 5) intentional statements (udāna); 6) contextual accounts (nidāna); 7) testimonies of realization (avadāna); 8) historical accounts (itivṛttaka); 9) accounts of former lives (jātaka); 10) detailed explanations (vaipulya); 11) wondrous discourses (abidhutadharma); and 12) definitive explanations (upadeśa). ↩

-

bye brag bshad mdzod, i.e. Mahāvibhāṣā, a major Abhidharma treatise of considerable length which was translated into Chinese but did not exist in Tibetan until the twentieth century. ↩

-

'dzam gling rgyan drug. Sometimes these are listed as: Nāgārjuna, Āryadeva, Asaṅga, Vasubandhu, Dignāga and Dharmakīrti. ↩

-

rmad byung slob dpon. This usually refers to the two masters Śāntideva and Candragomin. ↩

-

Following gSung 'bum. This line is omitted in and therefore not included in other translations, which were all based on the earlier, bSam 'phel edition. The reference is to the eighteen major Mahāyoga tantras included within the Ancient Tantra Collection (rnying ma rgyud 'bum). ↩

-

i.e., Potowa Rinchen Sal (1027/31–1105), Chengawa Tsultrim Bar (1033/8–1103) and Puchungwa Zhönnu Gyaltsen (1031–1106). ↩

-

Reading as sa bkar. bSam 'phel: sa kar; gSung 'bum: sa dkar. ↩

-

The five founding fathers of the Sakya School were: Sachen Kunga Nyingpo (1092–1158), Sönam Tsemo (1142–1182), Drakpa Gyaltsen (1147–1216), Sakya Paṇḍita Kunga Gyaltsen (1182–1251) and Chögyal Pakpa Lodrö Gyaltsen (1235–1280). ↩

-

rDo rje gdan pa. This apparently refers to the 11th- century Indian master, also known as Amoghavajra and the Later Vajrāsana, who was a teacher of Bari Lotsāwa Rinchen Drak (1040–1112). ↩

-

i.e., Nigūma and Sukhāsiddhī. ↩

-

bSam 'phel: gseng lam; gSung 'bum: gsang lam. ↩

-

i.e., they are valid in direct perception, through inference, and through scriptural authority. ↩

-

bSam 'phel 5a: rnyed par dka' ba'i tshul la legs par bsam/ This line is missing in gSung 'bum edition. ↩

-

Following bSam 'phel: 'phen pa yin. gSung 'bum: 'phen pa yi. ↩

-

Following gSung 'bum: skyon med. bSam 'phel: rkyen med. ↩

-

Folllowing bSam 'phel: kun gyi bsrungs. gSung 'bum: kun gyis blangs. ↩

-

i.e., the four powers of repentance, antidotal action, restraint and support. ↩

-

sems gnas pa'i thabs dgu: 1) settling the mind, 2) regularly settling, 3) continually settling, 4) fully settling, 5) taming, 6) pacifying, 7) thoroughly pacifying, 8) focusing one-pointedly, and 9) settling in equanimity. ↩

-

1) laziness, 2) forgetting the object of focus, 3) dullness and agitation, 4) not applying the antidote due to being too relaxed, and 5) applying the antidote again and again because one is too tightly focused and not content simply to rest. ↩

-

'du byed brgyad. 1) aspiration, 2) exertion, 3) faith, 4) pliancy, 5) mindfulness, 6) vigilance, 7) attention, and 8) equanimity. ↩

-

The eight extremes of conceptual elaboration are the views that phenomena 1) cease, 2) arise, 3) are non-existent, 4) are permanent, 5) come, 6) depart, 7) are multiple and 8) are singular. ↩

-

i.e., copying texts, making offerings, giving charity, studying, reading, memorizing, explaining, reciting aloud, contemplating, and meditating. ↩

-

This is a reference to a king who was a contemporary of Buddha Kāśyapa and had a number of prophetic dreams. During one of these he saw a cloth torn into eighteen pieces, which was interpreted as a prophecy that Buddha Śākyamuni's disciples would form eighteen different schools. ↩

-

Following bSam 'phel: phyi nas. gSung 'bum: phyi nang. ↩

-

This was the Indian diplomat Apasaheb Balasaheb Pant, also known simply as Apa Pant (1912–1992). ↩